I wanted to share one of my favorite college papers, in which I contrasted Henry David Thoreau's celebrated individual communion with land against the Dakota's collective kinship with Bdote and desperate resistance to dispossession, using this to point to how American freedom was built on the silencing and exile of indigenous protest.

Walden and Bdote:Land, Protest, and the Forgotten Cost of American Freedom

Jade Michael Thornton

University of Minnesota

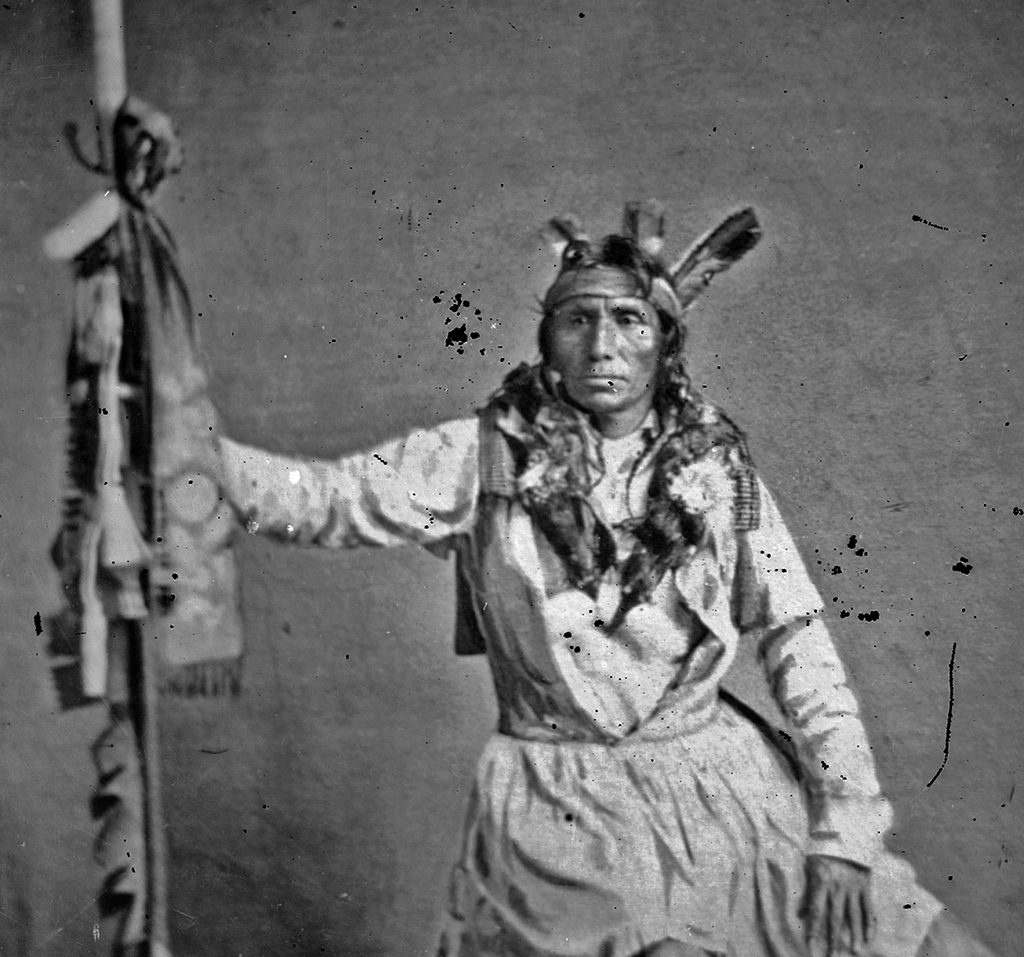

In June of 1861, a steamboat3 carrying Minnesota's governor, political dignitaries and a group of white observers drew up at the Redwood Agency for what would become the last peaceful treaty payment to the Dakota people4 before betrayal, starvation, and violence made such ceremonies impossible.5 7 8 Among those present was Henry David Thoreau, the New England naturalist, whose brief visit made him an accidental witness to rising Dakota desperation. Listening amid a crowd more interested in official rituals than in Dakota grievances, Thoreau noted quietly in a letter, "The most prominent chief was named Little Crow. They were quite dissatisfied with the white man's treatment of them & probably have reason to be so."5 7 9 That mundane remark anticipated the eruption of war and exile that would engulf Little Crow's world only a year later. Their paths crossed by chance at a fulcrum of Minnesotan and American history, each emblematic in vastly different ways, of resistance to injustice and the meaning of relationship to land.10

The coincidence of Thoreau's brief encounter with the Dakota underscores the depth of the divide between their worlds. For Thoreau, Walden Pond represented a sanctuary for moral renewal and principled dissent; he became both model and myth, celebrated as America's first great interpreter of nature and a paragon of individual conscience.11 13 However, the legend of solitary resistance often masks how Thoreau's insight was limited by mid-19th-century New England's assumptions about property and the hierarchy between settlers and Native peoples. Beneath his critique of progress, Thoreau operated within a society deeply invested in land as commodity and shaped by settler colonial beliefs, which constrained the possibilities of his vision even as he resisted its mainstream currents. For the Dakota, by contrast, land was neither backdrop nor resource, but a living relative, the foundation of kinship and language.10 14 Their center was Bdote,15 the confluence of rivers where, as creation stories recount, the Dakota people emerged from earth and water and began a relationship of mutual care and obligation.14 The United States did not see land this way. As expansion accelerated, the nation demanded cessions, negotiated and broke treaties, and enforced a language of ownership foreign to Dakota understanding, until patience gave way to the desperate calculus of survival.

America's story has depended on the systematic elimination of Native presence, physically and symbolically, a process by which the dominant settler society secures itself through the construction of the "other" who can be dispossessed.17 18 Dakota presence and removal functions as the setting of American origins—a setting that must not speak for itself but serves as the shadow on which national self-creation rests. Thoreau's dissent is canonized as a noble conscience, while the Dakota resistance is written out of national memory. A close study of Thoreau's tradition and that of the Dakota reveals sharply different relationships to land, contrasting forms of protest, and profoundly unequal consequences for resistance. Dakota resistance to unjust government in 1862 should be recognized as legitimate resistance, standing alongside Thoreau's celebrated acts of civil disobedience. The ongoing exclusion of the Dakota from the national canon reveals a contradiction at the heart of the United States: a nation born in rebellion, it upholds ideals of liberty for some by displacing and silencing others. Reckoning with Dakota resistance and its consequences is essential to confront how the American promise of liberty has depended on the denial of justice to those it casts outside its boundaries.

Land and Meaning

The Dakota, who gave Mni Sota Makoċe its name—"land where the waters reflect the skies"—live in a world where land, origin, kinship, and spirit are inseparable.14 19 Their understanding of land begins at Bdote, the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers,20 from which traditions say the Dakota people first arrived, formed from the clay at Maka Ċokaya Kiŋ, the Center of the Earth.14 16 19 Here, stories and obligations to the land are passed through language, ceremony, and place-names that mark ancient belonging and ongoing return, even in exile. Identity is rooted in caring for land as a living relation; the Dakota word for "mother" and "earth" are the same, "Ina."19 This equivalence is no metaphor, Dakota identity is rooted in caring for land and returning—even after exile.14 19 21

For the Dakota, land is not a commodity but a relative—an ongoing being, woven into story, subsistence, and belonging. The attempt by the United States to extract "cessions," to convert place into property sold to the exclusion of all but the owner, was both a legal strategy and a form of cultural violence. Treaties deliberately reframed the relationship to land using the language of ownership and exclusive title in order to justify dispossession. This was facilitated by translation choices: missionary Stephen Riggs, responsible for the Dakota-language versions of two pivotal 1851 treaties, selected words that purposely obscured the American legal meanings of "to cede," "to sell," or "to relinquish."22 His Dakota translations substituted words meaning "to give up" or "to throw away," concepts which do not make sense when applied to Ina Maka, Mother Earth, making it impossible for Dakota signers to grasp the full legal consequences.19 Cheyfitz observes, "In traditional Native American cultures there are persons, but no 'individuals.'… there, traditionally, is no notion of property. For the idea of property depends on the possibility of an individual relation to the land."18 This fundamental difference gave the U.S. legal system the advantage, using mutually unintelligible language and intention to unravel Dakota kinship, history, and hope, and making dispossession not just a matter of force but of deliberate misunderstanding written into law.

Thoreau's relationship with land emerges out of a different heritage, though it is marked by its own deep yearning and critique of his culture's trajectory. Troubled by a society in which "men have become the tools of their tools," he sought refuge at Walden to discover a truer, more vital existence.1 His famous retreat was not an escape into wilderness but an effort to "live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life," and to let the land teach him what civilization obscures.1 13 Walden Pond, for Thoreau, was "earth's eye, looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature."1 In passages that border on reverence, Thoreau imagines the pond as a living interlocutor, a mirror for self-examination, and a source of moral renewal and insight.

Thoreau's experiment rested on daily acts of tending and listening to the land. The chapters "The Ponds" and "Solitude" unfold as meditations on how land shapes mood, vision, even ethical possibilities. Seasons, dirt, and water do not merely support life—they instruct and humble their visitor. Buell observes that Thoreau's project becomes "one of fitful, irregular, experimental, although increasingly purposeful, self-education in reading landscape and pondering the significance of what he found there."11 The land's power is further acknowledged in Thoreau's restless awareness of loss: he mourns clear-cut forests and industrial progress as an abstract evil, and a specific diminishment of nature's capacity to nurture the spirit.

If Thoreau's retreat is a protest against his nation's increasing alienation from land, it is also a meditation on the contradictions of his role as a white settler. He pursues kinship with place through experiment and labor, but his belonging remains partial and chosen, a project one may freely attempt or put aside. Unlike the Dakota, for whom loss of land is a wound at the root of being, Thoreau's losses are encountered and mourned, but never cut to the core of the sense of self or community. His vision of harmony with land is shaped by his 19th-century New England assumptions about property and autonomy, even as he seeks to outgrow them. Sayre observes that while Thoreau "sometimes claims kinship with the land, his writing is an ongoing quest to approach land on its own terms," marked by aspiration and limitation.23

The Dakota and Thoreauvian ways of being with land thus reveal two radically different ontologies—the first grounded in continuity, kinship, and mutual obligation; the second experimental, reflective, and forever reaching for a belonging it can envision but cannot fully enact. Their fleeting meeting at the Redwood Agency and the divergence of their fates a year later expose the cost when those with the power to define property limit who is allowed to belong and whose losses are remembered.

Desperate State of Mind

Dakota resistance followed years of deprivation and forced endurance. Patience was deep-rooted; for generations, Dakota moved with the seasons, caring for land and kin. Treaties and reservations ended this, confining families to reserved land, and dependence grew as a result. The 1851 treaties of Mendota24 and Traverse des Sioux tied survival to annuity payments, which were often late or siphoned by traders. Big Eagle later recounted, "The Indians bought goods of [the traders] on credit, and when the government payments came the traders were on hand with their books, which showed that the Indians owed so much and so much, and as the Indians kept no books, they could not deny their accounts, but had to pay them, and sometimes the traders got all their money."2

By the summer of 1862, Dakota patience was stretched thin. A failed harvest, an unusually harsh winter, and the absence of meaningful government support left many weakened by hunger. Still, following the rhythms imposed by outsiders, the bands gathered in hope around the agency each year. When rumors that the payment, already weeks late,25 might not arrive at all, traders closed their doors while families had nothing to eat. Sarah Wakefield, a white witness at the Upper Sioux Agency, saw that "these poor creatures subsisted on a tall grass which they find in the marshes, chewing the roots, and eating the wild turnip... I know that many died from starvation or disease... It made my heart ache."26 Good Fifth Son would later recall, "a starving condition and desperate state of mind."2

Debate turned bitter in councils and the soldiers' lodge, historically a group of hunters, increasingly called for violent action. Years of delegations, attempted adaptation, and patience had only resulted in humiliation and hunger. The 1862 crisis was the result of broken promises. "Every one of the treaty negotiations... between Dakota people and the United States government were immoral and fraught with corruption," Waziyatawin writes, "but in the end, even the ridiculous terms of the treaties were moot because the government violated every one."14

Forms of Resistance

Recognition shapes protest. Thoreau's testimony and refusal were legible to the nation; the Dakota protest, however lawful, was ignored. Effective resistance required a form that the dominant society would recognize. Thoreau's 'Civil Disobedience' offered a refusal easily identified as moral. Thoreau, questioning state complicity in slavery and war, writes, "We should be men first, and subjects afterward... The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right."1 Later dissenters, including Gandhi and King, read from Thoreau's script to transform the public conscience.27 28 29 Their protests worked precisely because the nation (however reluctantly) could reflect and, sometimes, revise itself.

The Dakota protested first through diplomacy and speeches,2 14 19 but these recognizable forms could not be "heard" as legally meaningful. As Cheyfitz notes, this was by design: "There was also a great oral tradition among many tribes concerning the provisions of the treaties and their meaning. … Courts had declared that this oral tradition could not be used by Indians in cases that involved treaties, and that only the writings and minutes taken by the government secretaries and officers would qualify, since they were considered 'disinterested parties.'"18 The boundary between celebrated and suppressed protest in American memory is marked by the nation's willingness to label certain acts as "civil" and thus worthy of recognition. As Erickson and others have shown, this distinction is not neutral: "civil disobedience" is often defined to exclude actions by marginalized groups whose grievances exceed what the dominant society is prepared to see or address.28 The concept of "civility," then, functions as a gatekeeping tool, policing the forms of protest granted legitimacy and relegating all others to silence or infamy. This selective embrace of dissent reveals not universal principles, but a defensive logic protecting the status quo of property and order; it ensures that only those challenges compatible with national self-image are ultimately remembered as American.

Some among the Dakota pressed forward in an attempt to survive, adopting farming, building houses, and cultivating land. But this "sensible course," as Big Eagle called it, only earned them the resentment of other bands and the derision of government officers.2 19 "The whites were always trying to make the Indians give up their life and live like white men—go to farming, work hard and do as they did—and the Indians did not know how to do that, and did not want to anyway," Big Eagle explained.2

Denial of recognition shaped the war's tragic ignition. In August 1862, following years of deprivation, an argument among four young Dakota men about stealing eggs escalated to the murder of five settlers in Acton, Minnesota.2 8 30 Though this act was indefensible, those responsible knew it would doom their people: state violence would make no distinction between guilty individuals and the fate of an entire people. Big Eagle recalled, "It began to be whispered about that now would be a good time to go to war with the whites and get back the lands. It was believed that the men who had enlisted [for the Civil War] had all left the state, and that before help could be sent the Indians could clean out the country, and that the Winnebagoes, and even the Chippewas, would assist the Sioux."2 Anticipating collective punishment, Dakota leaders called a council to debate whether any future remained in patience or restraint.

At Little Crow's house—just hours after the Acton murders—the council did not celebrate revolt. Instead, it was a reckoning with years of repression and the glimmer of hope for recovering their taken land. Elders like Traveling Hail urged caution; others pressed for violence, seeing it as inevitable. The people turned to Little Crow (Taoyateduta), not as a willing commander but as a last, reluctant leader. His response carried grief, not glory:

Braves, you are like little children; you know not what you are doing... We are only little herds of buffalo left scattered; the great herds that once covered the prairies are no more. See!–the white men are like the locusts when they fly so thick that the whole sky is a snowstorm... Kill one–two–ten, and ten times ten will come to kill you. Count your fingers all day long and white men with guns in their hands will come faster than you can count… Yes; they fight among themselves, but if you strike at them they will all turn on you and devour you and your women and little children…2 32

He warned of ruin, but in the end agreed to share his people's fate:

Taoyateduta is not a coward; he will die with you.2 31 32

By dawn, war became a reality. Dakota warriors attacked agency posts and settlements along the Minnesota River. The uprising that followed was swift, brutal, and impossible to contain; it was the collective response of a people who, for all their prior appeals to justice, had been driven to the end of endurance.33 The eruption of war on August 18 was not a heroic rebellion but the consequence of a willfully ignored protest.8 10 19 Where Thoreau's disobedience could eventually be read as testing the republic's conscience, the Dakota's became proof of American innocence. The dominant order legitimates only forms of resistance it is willing to see; the rest are lost to law and memory.27 28 34 35 Dakota protest at the limits of endurance revealed the costs of American justice: costs written in the lives and land of the unseen. What followed made clear that the winners drew the boundary between legitimate protest and criminality through violence, law, and forgetting.

Contradiction at the Heart of America

The American project of self-creation, defining and redefining national identity, has always depended on principles of liberty and retroactively drawing boundaries around which voices and memories are permitted to matter. Thoreau's solitary act of resistance, refusing to pay taxes to a state complicit in slavery and war, became enshrined as an emblem of the nation's highest values: individual conscience, principled dissent, and the celebration of questioning authority. His place in memory was secured because his protest could be absorbed into the mythology of American freedom. It was held up as proof that the nation welcomes and ultimately honors those who resist injustice, so long as their protest fits within familiar forms.

As Kaplan observes, "American exceptionalism [is] defined as inherently anti-imperialist, in opposition to… empire-building," even as conquest of Native land—and the disavowal of that history—remains a recurring requirement of national identity.36 Those who cannot be so recuperated, like the Dakota, remain consigned to absence, their protest rendered unintelligible by the shape of American memory.

For the Dakota, resistance was not a matter of experiment or choice. It was compelled by a foreign nation's encroachment and broken promises, as years of negotiation and legal petitions were met with indifference or betrayal.2 When hope was finally exhausted, the Dakota's acts were punished as crimes by military tribunals, in stark contrast to how American dissenters like Thoreau were ultimately canonized.8

The doctrine of "domestic dependent nations" relegated tribal sovereignty to a status always subject to Congressional authority, enabling the United States to unilaterally break treaties and redefine or dissolve Native rights whenever expedient.34 The Dakota case is emblematic of how this legal structure, repeatedly upheld by American courts, applied to all Native societies whose continued presence challenged the national project of settler self-creation.

Cheyfitz characterizes this dynamic as a "self-serving logic" built into American law and the story it tells: "This 'history of America' is, of course, generated by the same 'principles' that it 'proves': the principles of Western law, which are, precisely, those of property with its foundation in the notion of title. This history, then, is based on a totally self-reflexive, or self-serving, logic, the limits of which are the term property."18 The American ideal of liberty has always relied on the exile or silencing of those whose relationships to land defied its boundaries. Manifest Destiny demanded the erasure of people whose kinship with place troubled the nation's chosen script.

Tragedy and Exile

The aftermath of the Dakota resistance brought neither justice nor peace. Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey proclaimed to the legislature, "The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the State."19 Words became policy: the state organized bounties for Dakota scalps and encouraged vigilantes to hunt any survivors. Federal authorities, facing pressure from settlers clamoring for revenge, organized mass military trials that sentenced 307 Dakota men to death, offering little pretense of due process (some trials were heard in as little as five minutes) and recognizing neither the context nor the legitimacy of their resistance.8 32 37

In Washington, President Lincoln confronted a settler populace demanding vengeance. He reviewed the court records to commute as many sentences as possible.

The president ordered a stay of all executions until he personally reviewed the trial transcripts. Sick at heart by the ongoing slaughter in the South, Lincoln had no appetite for mass hangings. He agreed with Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Dole that such actions would be "a stain on the national character." The president was also troubled by a recent meeting with [missionary] Bishop Whipple, who had eloquently laid out the history of abuses that finally culminated in violence. Lincoln was so moved that he pledged, "If we get through this war, and I live, this Indian system shall be reformed!"10

After the gallows, the punishment did not end. More than 1,700 Dakota men, women, and children were forced to a concentration camp below Fort Snelling, where hundreds died of disease and exposure through the winter. The next year, the state ordered the complete removal of the survivors, even those who had opposed the war. On their way out, they were subjected to humiliation and assault as townspeople lined the route in fury. Congress unilaterally annulled all Dakota treaties.38 39 Courts affirmed that Congress, within America's own legal inventions, had the right to break its word if it saw fit, anchoring the Dakota expulsion in law.

American triumph was built on the disappearance of peoples and stories. The aftermath of the Dakota resistance made clear that the victors drew the boundary between legitimate protest and criminality through violence, law, and selective forgetting. Memories of liberty were secured for some at the price of another's removal, and the nation's own ideals were entwined with exclusion and exile. Though the narrative of the Dakota has often been suppressed or disregarded, their voices persist, enduring in acts of protest, remembrance, and the ongoing struggle to be heard in their own homeland. The contradiction remains: a nation that celebrates dissent and justice, but only within the limits it chooses to recognize. To remember Dakota resistance as it truly was—not as a crime, but as a final, desperate reckoning with betrayal—is to expose the unresolved cost of American self-creation, a cost that neither Thoreau's searching conscience nor Little Crow's doomed warning could ultimately redeem or erase. Only in facing the stories that have been written out, yet still refuse to fade away, can the depths of the long-favored promise and the wounds beneath it come fully into view.

Glossary and People

- Alexander Ramsey

- (1815-1903) Governor of Minnesota during the Dakota War, who called for the removal or extermination of the Dakota following the conflict.

- bde

- lake (noun), going (verb).

- Bdewákhaŋthuŋwaŋ or Mdewakanton

- one of the tribes of the Isáŋyathi (Santee) Dakota (Sioux), of which Little Crow was a leader. Literally "people of the mystic lake" (Lake Mille Lacs).

- Bdote

- literally "confluence of rivers," also known as Maka Ċokaya Kiŋ, the center of the earth.

- Big Eagle (Wamditanka)

- (1827-1906) A respected Dakota leader and orator, whose account of the causes of the 1862 war is frequently cited. He participated in the conflict and later dictated his experience. He was among those pardoned by President Lincoln.

- Ȟaȟa Wakpa

- literally "River of the Falls", Mississippi River.

- Henry David Thoreau

- (1817-1862) American naturalist, essayist and philosopher. He championed individual conscience, simplicity and resistance to unjust government. Thoreau visited Minnesota in 1861 in an attempt to treat his terminal tuberculosis.

- Isáŋyathi, Isanti, Santee

- The Eastern Dakota, "dwells at the place of knife flint."

- Little Crow (Taoyateduta, His Red Nation)

- (c. 1810-1863) A prominent Bdewákhaŋthuŋwaŋ leader during the Dakota War. He became the reluctant leader of Dakota resistance following pressure from his people.

- Lower Sioux Agency, or Redwood Agency

- the federal administrative center for Dakota living on the lower (downriver) part of the Minnesota River.

- Maka Ina

- Mother Earth.

- mni

- water.

- Mni Sota Makoċe

- Minnesota, literally "land where water reflects the sky."

- Očéti Šakówiŋ

- Seven Council Fires, also called the Sioux.

- Sarah Wakefield

- (1829-1899) A white prisoner and survivor of the Dakota War, she provided a first-hand account of conditions in Dakota caps and the events surrounding the war.

- Sioux, or Nadouessioux

- The Sioux people, from the Ojibwe term Nadowessi meaning "little snakes."

- Sisíthuŋwaŋ

- one of the tribes of the Isáŋyathi (Santee) Dakota (Sioux). Literally "lake village people."

- Stephen Riggs

- (1812-1883) Presbyterian missionary and linguist who translated treaties for the U.S. government, often in ways that obscured critical legal meanings for Dakota signers.

- tipi

- lodge (noun), they live (verb).

- Traveling Hail (Wasuihiyayedan)

- An elder within the Dakota community, elected speaker in 1862, noted for counseling caution and restraint after the Acton murders.

- Upper Sioux Agency, or Yellow Medicine Agency

- the federal administrative center for Dakota living on the upper (upriver) part of the Minnesota River.

- Wabasha

- (c. 1816–1876) Principal chief of his Bdewákhaŋthuŋwaŋ band in 1862. Advocated for negotiation and adaptation with the U.S. government, striving for land security. After the war, he helped rebuild lives at the Santee Reservation in Nebraska.

- Waȟpékhute

- one of the tribes of the Isáŋyathi (Santee) Dakota (Sioux). Literally "leaf archers."

- wakaŋ

- holy, mysterious, sacred.

- Wakaŋ Tipi

- Dakota sacred site near present-day St. Paul, Minnesota.

- wakpa

- river, stream.

- Wakpa Mni Sota

- Minnesota River.

- Wanaġi Taċaŋku

- road of the spirits, the Milky Way.

- William Whipple (Bishop Whipple)

- (1822-1901) Episcopal Bishop of Minnesota and advocate for reform of the federal Indian system, he pleaded for clemency and justice for the Dakota with President Lincoln.

Brief Timeline

- 1805

- Treaty of St. Peters, also called Pike's Purchase, the Dakota cede small tracts at Bdote for the construction of Fort Snelling, and eagerly await this new trading opportunity.

- 1825

- Treaty of Prairie du Chien, establishing tribal boundaries and "spheres of influence."

- 1837

- [Second] Treaty of St. Peters, also called the White Pine Treaty, the Dakota ceded land east of the Mississippi.

- 1851

- Treaties of Mendota and Traverse des Sioux, the Dakota cede nearly all of their land and move to a reservation system in exchange for annuity payments.

- July 1845–September 1847

- Thoreau lives at Walden Pond.

- May 1849

- Thoreau's "Resistance to Civil Government" is first published in Aesthetic Papers.

- August 9, 1854

- Walden is published.

- 1858

- "Land Allotment" Treaties, reducing Dakota land to a small reservation along the Minnesota River (10 miles wide, 140 miles long), opening the rest of the land to white settlement.

- May 11–July 9, 1861

- Thoreau visits Minnesota in an attempt to relieve his tuberculosis.

- May 6, 1862

- Thoreau dies from tuberculosis.

- August 17, 1862

- Murder of five settlers at Acton, Minnesota.

- August 18, 1862

- Attacks on the Upper and Lower Sioux Agencies, and Redwood Ferry.

- August 22, 1862

- Main attack on Fort Ridgely.

- September 26, 1862

- Surrender of captives at Camp Release.

- December 26, 1862

- 38 Dakota executed at Mankato, Minnesota.

- February 16, 1863

- Congress passes an act that "all treaties heretofore made and entered into by the Sisseton, Wahpaton, Medawakanton, and Wahpakoota bands of Sioux or Dakota Indians, or any of them, with the United States, are hereby declared to be abrogated and annulled."

- July 3, 1863

- Little Crow is killed by a settler near Hutchinson while gathering raspberries.

Notes and References

- Thoreau, Henry David. Walden and Civil Disobedience. New York: Union Square & Co, 2023.

- Anderson, Gary Clayton, and Alan R. (Alan Roland) Woolworth. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

- The steamboat that carried Thoreau to the Redwood Agency in 1861 was named the Frank Steele after a man whose "flashing axe in the wilderness" symbolized the spirit of settler progress. Thoreau observed with wry detachment how the boat repeatedly rammed riverbanks and destroyed trees to navigate the winding waterway, offering a literal and comic description of American expansion crashing up against the land's contours.23

- The terminology used for Native peoples in North America varies considerably and is shaped by context, community preference, and scholarly convention. "Native American," "American Indian," "Indigenous," and "Native" are all in current use, and it is widely accepted best practice to name peoples in terms of their specific tribal or national identity whenever possible—for example, Dakota, Ojibwe, or Lakota.5 14 19 While the most linguistically precise representation may be "Dakȟóta" or "Dakhóta" (with diacriticals reflecting the Dakota alphabet), the plain form "Dakota" appears most consistently in both academic scholarship and within English-language writings by Dakota scholars themselves (see Waziyatawin, Westerman & White). The anglicized spelling is thus retained here for coherence with established scholarly usage and accessibility to a general audience, while always privileging Dakota perspectives and language where appropriate.

- National Museum of the American Indian. "Teaching & Learning about Native Americans," n.d. https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/faq/did-you-know.

- Harding, Walter. "Thoreau and Mann on the Minnesota River, June, 1861." Minnesota History 37, no. 6 (1961): 225–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20176368.

- Flanagan, John T. "Thoreau in Minnesota." Minnesota History 16, no. 1 (1935): 35–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20161165.

- Carley, Kenneth. The Dakota War of 1862. 2nd ed. St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

- In Thoreau's Minnesota notes, he records a "Dream Dance" put on at the request of Governor Ramsey at the 1861 agency gathering, but there is no documented evidence of this as a specific Dakota ceremony at that time. The "Dream" or "Drum Dance" later became part of new religious movements responding to dispossession and trauma, but Thoreau (like many observers) likely misunderstood the ritual, applying a misnomer from missionary or ethnographer sources to a Dakota ceremony whose meaning he did not grasp.23 19

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

- Buell, Lawrence. "Thoreau and the Natural Environment." In The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, 171–93. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521440378.013.

- Buell, Lawrence. "American Literary Emergence as a Postcolonial Phenomenon." American Literary History 4, no. 3 (1992): 411–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/489858.

- Schneider, Richard J. "Walden." In The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, 92–106. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521440378.008.

- Waziyatawin. "Maka Cokaya Kin (The Center of the Earth): From the Clay We Rise." Paper presented at University of Hawaii Manoa International Symposium 'Folktales and Fairy Tales: Translation, Colonialism, and Cinema', Honolulu, Sept 23-26, 2008. http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/16456.

- The Dakota word Bdote (or Mdote) means "confluence" and refers specifically to the area around the meeting of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The difference in spelling (B- vs. M-) arises from dialect variation and changing conventions for transcribing Dakota—contemporary usage increasingly prefers "Bdote."14 16

- White, Bruce. "Bdote/ Mdote Minisota: A Public EIS Continues." MinnesotaHistory.Net (blog), February 26, 2009. https://www.minnesotahistory.net/staging/?p=169.

- Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native." Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409. doi:10.1080/14623520601056240.

- Cheyfitz, Eric. "Savage Law: The Plot Against American Indians in Johnson and Graham's Lessee v. M'Intosh and The Pioneers." Cultures of United States Imperialism (1993): 109-128.

- Westerman, Gwen, and Bruce M. White. Mni Sota Makoċe: The Land of the Dakota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

- The Dakota name for the Mississippi is Wakpá Taŋka (Great River) or Ȟaȟa Wakpá (River of the Falls). The name Mississippi comes from the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) name Misi-ziibi, also meaning Great River.

- Gould, Roxanne, and Jim Rock. "Wakaŋ Tipi and Indian Mounds Park: Reclaiming an Indigenous Feminine Sacred Site." AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 12, no. 3 (September 2016): 224–35. https://doi.org/10.20507/AlterNative.2016.12.3.2.

- Missionary Stephen R. Riggs, the main translator for the Dakota-language text of the treaty of Traverse des Sioux (1851), intentionally substituted neutral or ambiguous Dakota verbs in place of critical American legal concepts. For example, the English treaty states the Dakota "agree to cede, sell, and relinquish all their lands." Riggs translated "cede" as "erpeyapi" (to give up, throw away, lose), a term without the legal finality of English property law, a word he also used for describing money that would be set aside for farming equipment. Meanwhile, "sell" and "relinquish" were treated similarly, with Riggs using everyday Dakota phrasing that did not carry the sense of permanent transfer. The Dakota had no concept of exclusive title to land, and this linguistic mismatch ensured they could not grasp what they were supposedly agreeing to.19

- Sayre, Robert F. Thoreau and the American Indians. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- The historical agreement commonly called the "Treaty of Mendota" is referred to by this official name because that is its title in United States government records and legal references. While "Mendota" is an anglicized rendering of the Dakota word Bdote, using the legal designation also distinguishes this specific 1851 treaty from other agreements and references to the place itself.16 19

- The 1862 annuity for the Dakota was delayed in part by a debate in Washington over whether it should be sent in gold or the new "greenbacks" (paper money), a monetary drama that further illustrates how distant policies could devastate local life. In a tragic irony, the $71,000 in gold finally arrived at Saint Paul the day before the murders at Acton, and would arrive to Fort Ridgely (the military camp protecting the agencies) several days later—too late to prevent the ongoing war.8

- Wakefield, Sarah F, and June Namias. Six Weeks in the Sioux Tepees : A Narrative of Indian Captivity. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

- Reddy, Saahith. "Thoreau's Civil Disobedience from Concord, Massachusetts: Global Impact." Frontiers in Political Science 6 (October 2, 2024). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1458098.

- Erickson, Evie. "Investigating the Meaning and Application of Civil Disobedience Through Thoreau, Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr." The Nonviolence Project. University of Wisconsin-Madison, March 16, 2024. https://thenonviolenceproject.wisc.edu/2024/03/16/investigating-the-meaning-and-application-of-civil-disobedience-through-thoreau-gandhi-and-martin-luther-king-jr/.

- Hendrick, George. "The Influence of Thoreau's 'Civil Disobedience' on Gandhi's Satyagraha." The New England Quarterly 29, no. 4 (1956): 462–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/362139.

- While the murder of five settlers at Acton on August 17, 1862, is often cited as the direct cause of war, underlying conditions made violence an ever-present risk. Dakota survivors and many settlers alike understood this event not as the origin, but as the moment when unbearable injustices boiled over—though the leaders who chose violence did so reluctantly and with awareness of likely catastrophe.2 8

- Despite being widely depicted in frontier myth as a bloodthirsty war chief, Little Crow (Taoyateduta) was, in fact, a complex and often conflicted leader. He succeeded his father as chief only after a violent dispute left him with both wrists shattered by gunfire; for years, he advocated for adaptation and peaceful coexistence, attending church services, negotiating in Washington, and even taking up farming. His oratory was legendary, and his warning to the war council in August 1862 was later remembered word-for-word by his son, Wowinape, and corroborated by other Dakota witnesses. In an unusual twist of fate, after the war forced him into exile, Little Crow was killed while picking raspberries with his son near Hutchinson, Minnesota. His scalp and remains were displayed for decades as war trophies in Minnesota museums, before finally being returned to his descendants for proper burial in the 1970s—a potent symbol of the long afterlife of memory and erasure in the story of Dakota resistance.2 10

- Michno, Gregory, ed. Dakota Dawn: The Decisive First Week of the Sioux Uprising, August 17-24, 1862. New York: Savas Beatie LLC, 2011.

- Fort Ridgely was among the obvious targets, and would be attacked twice in the coming weeks. Coincidentally, Fort Ridgely was named after two U.S. Army officers who died in the Mexican-American War: Major Jefferson F. Ridgely and Lieutenant Thomas L. Ridgely. The Mexican-American War itself was among the government injustices that prompted Thoreau's "Civil Disobedience," as he refused to pay taxes to a government waging what he considered an immoral conflict. Built in 1853 on the Minnesota River, Fort Ridgely became a crucial defensive post during the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, serving as the main refuge for white settlers and a central target during the conflict's early battles; its survival prevented a wider collapse of settler control in the region. Notably, contemporary accounts suggest that if the Dakota had attacked the fort immediately following their early victories—before reinforcements arrived—they could have overrun it and altered the course of the war.1 8

- Duthu, N. Bruce. American Indians and the Law. The Penguin Library of American Indian History. London: Penguin Books, 2009.

- Byrd, Jodi A. The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. First Peoples: New Directions in Indigenous Studies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

- Kaplan, Amy. "Left Alone With America: The Absence of Empire in the Study of American Culture." In Cultures of United States Imperialism. New Americanists. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.

- Many of the military trials that followed the Dakota War of 1862 were shockingly brief, sometimes lasting just minutes. One reason for this haste was that Dakota defendants, unfamiliar with American criminal proceedings, often freely admitted participation in battles, believing they were answering honestly about what they considered legitimate acts of war against soldiers. Unaware that they were being tried as if these actions were cold-blooded murder rather than recognized acts of war, they did not see the need to conceal their involvement.8 10

- Vogel, Howard. "Rethinking the Effect of the Abrogation of the Dakota Treaties and the Authority for the Removal of the Dakota People from Their Homeland." William Mitchell Law Review 39, no. 2 (January 1, 2013). https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol39/iss2/5.

- In the wake of the Dakota War, Congress passed legislation in February of 1863 unilaterally abrogating all treaties with the Dakota. "Abrogation" refers to the formal repeal or annulment of a law or agreement; in this case, Congress declared that all obligations to the Dakota under previous treaties were void and redirected remaining payments to compensate white settlers for damage caused by the war. According to U.S. legal doctrine, Congress reserves the power to unilaterally end treaties with Native nations—essentially disregarding the original nation-to-nation status and legal promises—by simple legislative act, even without the consent of the affected Native party. The Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld this authority, holding that "plenary power" over Indian affairs resides with Congress, regardless of prior agreements. The Act of February 16, 1863 not only declared the treaties abrogated but also seized Dakota lands within the State of Minnesota. The Dakota, for their part, had no legal recourse to prevent this breach; the federal government's power to break its own word was built into the legal system governing U.S.-Native relations.38 40

- U.S. Congress, An Act for the Relief of Persons for Damages sustained by Reason of Depredations and Injuries by certain Bands of Sioux Indians, 37th Cong., Act, February 16, 1863.

- Dakota Online Dictionary, https://dictionary.swodli.com/index.html.

- Scott County Historical Society. "Thoreau's Journey along the Minnesota River," May 22, 2019. https://www.scottcountyhistory.org/blog/thoreaus-journey-along-the-minnesota-river.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. ReVisioning American History. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.